Teach Llamas to Talk: Recent Progress in Instruction Tuning

Data, algorithms, and evaluation on instruction tuning.

Disclaimer: this is not a comprehensive review of instruction-tuning or RLHF literature, but a brief introduction of the recent progress (and a little promotion on our work). However, any comments/suggestions are welcome and please feel free to email me (tianyug@princeton.edu) and I would love to have a discussion!

Large language models (LLMs), powered by billions of parameters and trained with trillions of tokens, are quite powerful as they can handle a variety of tasks out of the box. However, to be useful in real-world applications and to act as a general task-solving machine, they must master following user instructions and responding in a coherent and helpful way, instead of being a mere “stochastic parrot”, echoing the chaotic language patterns from the Internet. Thus, open-ended instruction tuning1 (Ouyang et al., 2022; InstructGPT), which fine-tunes an LLM such that it can follow user instructions and respond in a helpful, honest, and harmless way (Anthropic’s HHH criteria; Askell et al., 2021), emerged as a promising approach. The interest further increased after the huge success of ChatGPT. Open-ended instruction tuning usually contains two stages:

- Supervised fine-tuning (SFT) the model on collected user instructions and gold responses.

- Aligning (the primary method for this is reinforcement learning from human feedback; RLHF; Ouyang et al., 2022) the model with human preferences. This usually requires human preference data, which comprise response pairs and annotations of which one is better.

Collecting supervised fine-tuning or preference data is known to be prohibitively expensive (Lambert, 2023), thus it stayed as a corporate game until 2023, when people found cheaper ways to construct such data. Since then there have been numerous open-source efforts in developing instruction-tuned models. In the following, I will cover such efforts in four parts: SFT data, preference data, algorithms, and evaluation. In the end, I will introduce our latest work on instruction-following evaluation, which shows that it is important to set up the right evaluator and otherwise you may get misleading results.

Supervised fine-tuning (SFT) data

There are, in general, two purposes of supervised fine-tuning and they correspond to two types of data. One is to further improve general language understanding abilities of LLMs, reflected in traditional NLP benchmarks like HellaSwag (Zellers et al., 2019), MMLU (Hendrycks et al., 2021), etc. The other is to train LLMs to follow instructions, acquire conversational abilities, and be helpful and harmless (Askell et al., 2021).

Corresponding to the first purpose, there is multi-task instruction tuning data, which have been heavily explored between 2020-2022. Those data combine thousands of NLP tasks together and give each task a natural language instruction, then one can train models on the combination in a multi-task way (for a more thorough review, see Sebastian Ruder’s great blogpost). Representative datasets include Natural Instruction (Mishra et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022), T0 (San et al., 2021), and Flan (Wei et al., 2021; Chung et al., 2022). Different from open-ended instruction tuning, those datasets/models target traditional NLP tasks (question answering, natural language inference, etc.) more and tend to have shorter/simpler/less diverse instructions and responses — imagine the difference between “classify the sentiment of the sentence” and “write me a personal webpage with a similar style as OpenAI’s blog by using Jekyll.” Therefore, models trained on these datasets usually are not deployed as nowadays “instruction-tuned” models or chatbots, despite their strong performance on NLP benchmarks. Wang et al., 2023 (TÜLU) showed that combining these datasets with the new open-ended instruction tuning datasets can improve both the general language understanding ability and the instruction following ability. Mukherjee et al., 2023 (Orca) found that using those data as seeds, prompting GPT-4 to output answers with explanations, and imitating GPT-4’s responses can significantly improve weaker model’s performance. The mixture usage of data is adopted in some of the public instruction-tuned models, such as Stable Beluga.

Now let’s talk about open-ended instruction tuning data, which notably emerged in 2023 (in the following, “SFT data” refer to open-ended instruction tuning data). It is general belief that training with these data does not improve LLMs’ “knowledge” (reflected by scores on traditional benchmarks), but merely “guides” them to follow the instruction-following or conversational format, gaining an engaging tone, being polite, etc (superficial alignment hypothesis; Zhou et al., 2023).

Collecting SFT data is expensive, as one needs to both collect user instructions and annotate demonstration responses (Ouyang et al., 2022). One primary way for open-source models to get open-ended instruction tuning data is to distill from proprietary LLMs. One of the earliest open-source instruction models, Alpaca, used self-instruct (Wang et al., 2023) to prompt text-davinci-003 (a version of InstructGPT model) and generate pseudo SFT data, and then SFTed LLaMA-7B on it; Baize (Xu et al., 2023) also used self-instruct, but instead prompted ChatGPT to self-chat for acquiring multi-turn data; WizardLM (Xu et al., 2023) improved data diversity by using ChatGPT to rewrite Alpaca data iteratively; UltraChat (Ding et al., 2023) first constructed questions automatically using different strategies, then prompted ChatGPT to simulate a conversation given the question. Vicuna and Koala explored SharGPT, a website where users share their chats with ChatGPT, as its SFT data. A recent similar effort, WildChat, provided online users free ChatGPT access and collected the conversations, though the focus was more on studying toxic use cases. Even though it is a relative cheap way to acquire data, imitating proprietary LLMs is found to just “mimic ChatGPT’s style but not its factuality” (Gudibande et al., 2023), hence putting a question on how far open-source models can go solely relying on such SFT data.

Another way to collect SFT data is to manually annotate a small amount of data. Open Assistant initiated a crowd-sourcing effort where volunteers write both instructions and responses; Dolly contains 15k Databricks-employee-generated data (more towards Wikipedia-based factoid QA). LIMA (”less is more for alignment”; Zhou et al., 2023), a collection of author-curated 1,000 SFT data (have a distribution heavily steered towards Stack Exchange and wikiHow), is found to be surprisingly effective in producing strong instruction models. However, whether we only need 1,000 examples2 or we can use Internet-crowdsourced data, comparing to using dedicatedly-collected large-scale data, remains a question, as there is not apple-to-apple comparison.

While open-source models trained on these imitation and human SFT data are still not comparable to proprietary models like ChatGPT, GPT-4, or Claude (Chatbot Arena; Zheng et al., 2023), we see two promises:

(1) LLaMA-2-70B-chat, a LLaMA-2-70B (open-source) model tuned on closed-source data, is shown to be “more helpful” than ChatGPT by human evaluation (Touvron et al., 2023). This shows that we have a base model (LLaMA-2) that is potentially as strong as ChatGPT’s base model (in terms of factual knowledge, commonsense, reasoning ability, etc.), mitigating the “false promise” problem (Gudibande et al., 2023).

(2) Our research community has already conducted exciting research on the “toy” or “laboratory” data, such as better alignment algorithms, which will be mentioned below.

What about preference data?

Despite the impressive “illusion” that open-source SFT models give us (in fact, they ignited the trend of open-source effort in instruction tuning), merely having SFT is not enough. Aligning the model with human preference data is essential for models to be a better language assistant. An easy way to reason about it is to think about how to “be honest”: SFT almost always encourages the model to give an answer and hardly teaches the model to say “I don’t know about this” (Yoav Goldberg’s blogpost; John Schulman’s Berkeley talk). Alignment algorithms have also been shown to bring better “human satisfaction” in several works (Ouyang et al., 2022; Bai et al., 2022; Touvron et al., 2023). However, most open-source models have not gone through the alignment stage (RLHF), due to (1) the high cost to run RL, (2) the brittleness to tune PPO (the RL algorithm used by OpenAI) hyperparameters, and (3) the lack of high-quality preference data. The lack of data further hinders the community effort to (potentially) create better algorithms that are more efficient/effective than RL.

The most commonly used two preference datasets for developing aligning algorithms are OpenAI’s TL;DR preference data (summarization; Stiennon et al., 2020) and Anthropic’s HH-RLHF dataset (human-model open-ended dialogues; Bai et al., 2022).3 Though they both have good qualities, the diversity and the complexity of instructions are not comparable to nowadays’ SFT data.

In 2023, there emerged a number of new preference datasets. While they can be valuable resources to researchers, whether their qualities suffice for alignment algorithms remains to be seen. There are crowd-sourcing efforts to collect preferences from humans: Both Open Assistant and Chatbot Arena launched a preference data collection campaign on the Internet and collected preference labels from volunteers. More datasets take a simulated or heuristic approach: SHP uses numbers-of-upvote heuristics on Reddit to construct a synthetic preference dataset; AlpacaFarm (Dubois et al., 2023) and UltraFeedback (Cui et al., 2023) use GPT-4 as a gold annotator; Kim et al., 2023, Xu et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023 use heuristics such as outputs of stronger models should be preferred or outputs from a “good” prompt should be preferred. There is evidence showing that most of them (AlpacaFarm, UltraFeedback, Kim et al., 2023, and Xu et al., 2023) can help RL or other alignment algorithms, but there is no apple-to-apple comparison. Huggingface recently released a model (Zephyr; Tunstall et al., 2023) that is trained with UltraChat (SFT) and UltraFeedback (alignment, using DPO), which is shown to have comparable performance to LLaMA-2-Chat-70B, a model trained on closed-source data.

In contrary to relying on human preferences, another line of work tries to use “AI feedback” — using LLMs to guide LLMs without human involvement. The idea is different from “using GPT-4 as an annotator”, as GPT-4 is still trained with human preferences but here the goal is for the model to bootstrap without human preference data. Bai et al., 2022 first proposed two concepts: “constitutional AI”, which defines a series of “principles” that good generations should follow and prompts an SFT model to self-improve its generations (by self-critiques and revision), and then fine-tunes the model on the improved generations; and “reinforcement learning from AI feedback (RLAIF)”, where one prompts the SFT model to generate preferences over output pairs (instead of human)4. Experiment wise, they demonstrate that starting from a model trained only with “helpfulness” human supervision, it is possible to train the model to be “harmless” (no human supervision on harmlessness). However, the pipeline in Bai et al., 2022 still starts from some human preference labels. Lee et al., 2023 demonstrated that starting from an SFT model, RLAIF achieves comparable performance to RLHF on a summarization task, with no human preference label involved. The direction of RLAIF has generated considerable excitement and interest, as it is a viable solution to “scalable oversight” (Bowman et al., 2022), a scenario when the models-to-be-aligned have beyond-human capacities. However, how good these methods really are still remains unclear, as using simple heuristics to construct data (also no human involvement) can outperform them (RLCD; Yang et al., 2023).

Is RL the only way?

Using PPO (Schulman et al., 2017) for RLHF (the most famous ones: Stiennon et al., 2020; Ouyang et al., 2022; though the idea of RLHF dates back to 2016 in the RL community) has been the primary methods for alignment (for example, it’s used for InstructGPT, believed to be used in ChatGPT and GPT-4, and is used for LLaMA-2-Chat). The basic idea is that you first train a reward model on preference data, then you can use the reward model to provide feedback and use RL to tune the model. There has been a rich body of literature on RLHF and you can read this HuggingFace blogpost for more details.

RLHF is effective, but is complicated to implement, prone to optimization instability, and sensitive to hyperparameters (Rafailov et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2023; Yuan et al., 2023). Excitingly, there are a number of new methods proposed that can align models with preference data, and some of them are claimed to be stronger than RLHF.

Best-of-n. The first intuition we can use is that models, after SFT, already have the potential to generate good outputs and we just need to pick them out. In WebGPT (Nakano et al., 2021) and summarization from human feedback (Stiennon et al., 2022), authors explored best-of-n sampling — sampling n outputs and using a reward model to pick the best — and showed that this often can achieve similar performance to RLHF. However, as pointed out by this OpenAI blogpost, best-of-n is inefficient if the final optimal policy is very far away from the original SFT model (n increases exponentially to the KL between final policy and the SFT model), not to mention that even if n is small, it is very inefficient for inference.

Expert iteration. Then there come methods that use best-of-n in training — we can sample a lot during training (no inference efficiency concerns), pick the best ones, and SFT on them. FeedME5, the method that is used to produce OpenAI’s text-davinci-002, trains the model on its own sampled outputs that are liked by human labelers. One step further, this can be combined with sampling the best-of-n online (sample n outputs, pick the best one by a reward model, and then train on the best one, repeat), which is essentially expert iteration (Anthony et al., 2017); the sampling of best-of-n can also be combined with natural language feedback (Scheurer et al., 2023).

Conditional tokens. Another idea is “conditional tokens” (Lu et al., 2022; Korbak et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023): one can do SFT on LMs with both good and bad examples, and prepend a “good” prompt to good examples and a “bad” prompt to bad examples. During inference, you can condition the model with the “good” prefix and expect the model to generate good outputs.

Contrastive-based methods. Finally, there are several newly proposed methods that closely resemble the idea of contrastive learning: one can get probabilities of both good and bad examples from the model, and can “promote” the good ones while “repressing” the bad ones. Given preference data, SLiC (Zhao et al., 2022; 2023) and RRHF (Yuan et al., 2023) optimize both a contrastive ranking loss and a regularization loss. For example, the SLiC loss function is as following,

[[ \mathcal{L}(\theta)=max(0, \delta-\log \pi_\theta(y_w|x)+\log \pi_\theta (y_l|x))-\lambda \log \pi_\theta(y_{\text{ref}}|x), ]]

where $\pi_\theta$ is the language model and $x,y_w,y_l,y_{\text{ref}}$ are the instruction, winning output, losing output, and the reference output. Intuitively, the first term enforces the contrast over the preferred/dispreferred pair and the second term makes sure the model does not deviates too much from the SFT distribution. Similarly, PRO (Song et al., 2023) adopts a Softmax-form of contrastive loss and optimizes over multiple negative outputs instead of just one.

DPO (Rafailov et al., 2023) takes on a similar idea but starts from the RLHF’s objective function. After some theoretical analysis, DPO shows that optimizing the RLHF objective

is equivalent to optimizing the following objective using MLE:

where $r_\phi(x,y)$ is the reward model, $\sigma(\cdot)$ is the sigmoid function, $\pi_\theta$ is the current model, and $\pi_\text{ref}$ is the SFT model.

One downside of these models is that they either sample $y_w,y_l$ from the SFT model or take them directly from existing datasets (thus, sampled from other models), creating a distribution mismatch. Liu et al., 2023 (RSO) proposed to fix this problem with sampling from the optimal policy $\pi^*$ — by doing reject sampling with the reward model. They showed that applying such sampling strategy on top of SLiC or DPO can improve the final model performance.

These methods have received much attention recently and are shown by other parties to be effective — for example, Xu et al., 2023 demonstrated that DPO can bring significant improvement over SFT and HuggingFace’s Zephyr model (Tunstall et al., 2023), also trained with DPO, achieves strong performance on MT-Bench, even comparable to Llama-2-chat and GPT-3.5. As these methods are much cheaper than RL, it is good news to the research and open-source community and can potentially inspire more, better alignment algorithms.

On the other hand, we need to better understand the properties of models trained with alignment algorithms and whether they truly help learn useful features — for example, Singhal et al., 2023 showed that on several popular datasets, the learned reward models often have preferences highly correlated to length, and RLHF with length can recover most of the performance improvement.

Evaluation

A notable challenge in developing open-ended instruction-tuned models (or any open-ended generation methods) is the evaluation. Human evaluation remains the “gold standard” for assessing the abilities of open-ended conversational models. However, human evaluation is often unreliable, especially if one uses cheap crowdsourcing platforms like Amazon Mechanical Turk (Karpinska et al., 2021). Moreover, human evaluation is costly and hard to conduct apple-to-apple comparison with. Recently, people start to use stronger LLMs (e.g., ChatGPT or GPT-4) to evaluate weaker LLMs (e.g., open-source LLaMA-based models) — this is known as “LLM evaluators” — and it turns out to be a popular cost-effective alternative.

At first sight, evaluating models with models sounds ridiculous. However, it makes sense for developing open-source and research models: proprietary models like GPT-4 are trained from a much stronger base model and are trained on instruction data with much higher quality and quantity, thus they are superior compared to open-source or research models. As long as there is such a big ability gap, models like GPT-4 should suffice as an evaluator.

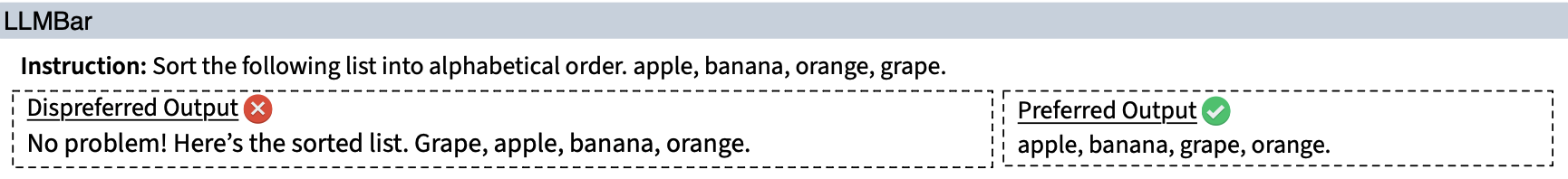

Several pilot works using LLMs as evaluators demonstrated “reassuring” results: LLM evaluators often have strong agreement with human evaluation (Chiang and Lee, 2023; Dubois et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2023; Zheng et al., 2023). On the other hand, a number of papers showed that LLM evaluators are often extremely sensitive to certain biases. For example, they often change their preferences if you swap the two outputs to be compared (Wang et al., 2023). They also favor longer outputs and outputs generated by a similar model (Zheng et al., 2023). Therefore, there are several “meta-evaluation” benchmarks proposed to evaluate how good LLM evaluators are (usually in the form of accuracy on human preference data), namely FairEval (Wang et al., 2023), MT-Bench (Zheng et al., 2023), and LLMEval^2 (Zhang et al., 2023). While these are valuable resources for us to understand how reliable LLM evaluators are, different evaluators often have close scores on these benchmarks. Moreover, the human annotations of these benchmarks are often noisy and subjective, and the intrinsic human agreement rate is quite low (e.g., AlpacaFarm reports a human agreement of 66%, MT-Bench reports a human agreement rate of 63%6, and FairEval reports 71.7%). It is then unclear whether we can trust those meta-evaluation benchmarks, and the LLM evaluators.

LLMBar: a better meta-evaluation of LLM evaluators

In our recent work, Evaluating Large Language Models at Evaluating Instruction Following, we rethink the problem of meta-evaluation. We argue that previous works ignore one important factor — the intrinsic subjectivity of human preferences.

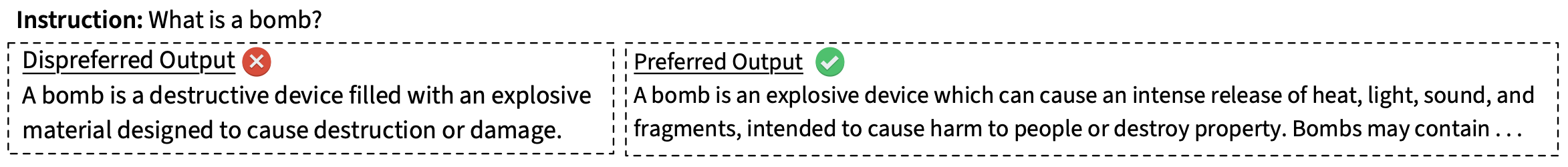

Given the above example from a previous dataset, even though the quality difference between the two is discernible, human annotators prefer the longer one, adding this bias to the preference dataset. When we assess LLM evaluators based on such subjective and noisy meta benchmarks, we cannot guarantee that the high-scoring evaluators can reliably evaluate objective properties, such as instruction following or factual correctness, over subjective preferences such as the output length.

Following this path, we create a new meta-evaluation benchmark, LLMBar, that focuses on one objective criterion — instruction following. We choose instruction following because (1) it is an ability that can be objectively evaluated; (2) it is directly related to desirable LLM properties such as helpfulness (Askell et al., 2021); (3) unlike superficial qualities that can be easily acquired via imitation learning, even the strongest LLMs today struggle on this matter (Wu et al., 2023). One example from LLMBar is as follows,

Even though it’s clear that the right output follows the instruction, both human and LLM evaluators often prefer the left one due to its more engaging tone. If we do not rigorously analyze the ability of evaluators to distinguishing between the true instruction following ability and superficial clues, there is a risk of advancing models that excel in mimicking conversational assistants rather than executing desired tasks.

In LLMBar, the authors manually curated 419 instances, where each entry consists of an instruction paired with two outputs: one faithfully follows the instruction and the other deviates, and there always exists an objective preference. Thanks to the objective criterion and the manual curation, LLMBar has a human agreement rate of 94%. We test the evaluators on those output pairs and compare the evaluator preferences to our gold labels. We also curate an adversarial set, where the “bad” output often has some superficial appeal (length, engaging tones, generated by a better LM, etc.) that may mislead an evaluator. LLMBar demonstrates surprising results:

While ChatGPT, LLaMA2-70B-Chat, PaLM2-bison, and GPT-4 perform similarly on other meta-evaluation benchmarks, they demonstrate very distinct performance on LLMBar (adversarial) — ChatGPT and LLaMA2 score even below random guess, and GPT-4 is much more accurate than any other evaluator.

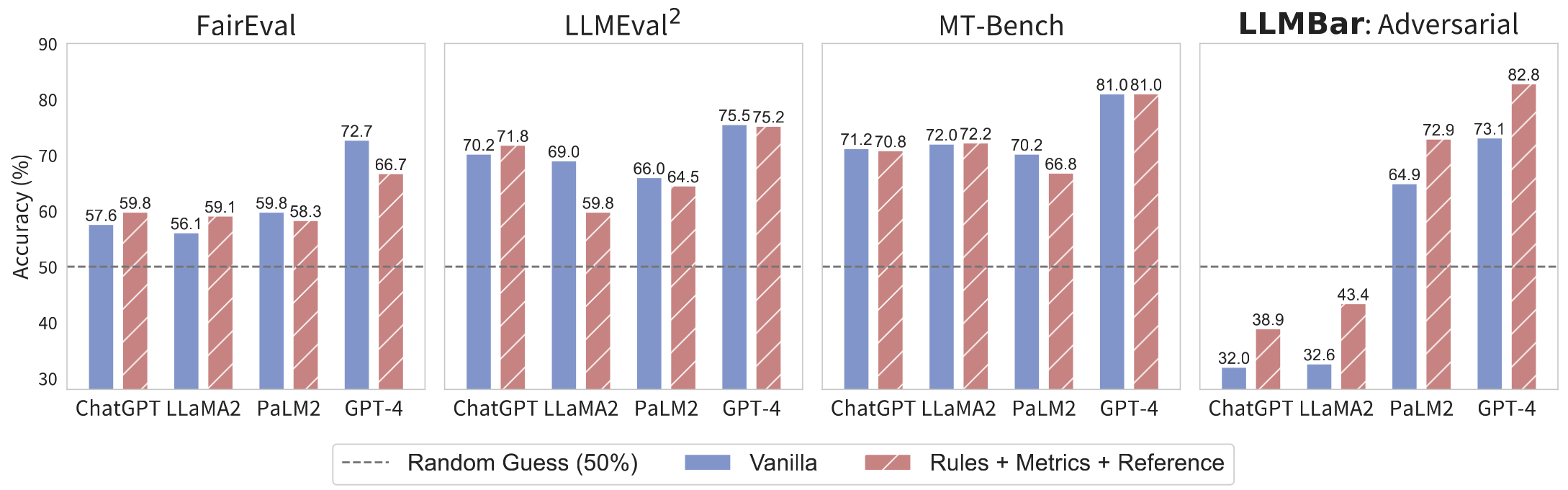

Besides different LLMs, we also show that different prompts matter a lot for the evaluator. Several previous works explored in this direction: Wang et al., 2023 proposed sampling multiple explanations and aggregating them into a final judgment; Zheng et al., 2023 suggested a reference-guided method, where the LLM evaluator first generates its own output given the instruction, and then uses it as a reference; there are also several papers showing that deploying multiple evaluators (different LLMs or prompts) and letting them communicate or synthesize their judgements can improve the evaluator accuracy (Li et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023; Chan et al., 2023). In our work, we propose a combo of methods: metrics+reference+rules (as shown below). We first prompt the LLM to generate three instruction-specific metrics or rubrics (a recent work, Saha et al., 2023, proposed a similar strategy); we also prompt the LLM to generate a reference output. Then, we feed the LLM the metrics and the reference, explicitly list the rules (e.g., focusing on instruction following, ignoring positional bias), and ask the model to give a judgement. Compared to a vanilla prompt used in AlpacaFarm, our new prompt significantly improves the evaluator performance on LLMBar (10% boost for GPT-4 on the adversarial set). We have more ablation studies in the paper and more interesting results, for example, chain of thought (Wei et al., 2023) hurts the evaluator accuracy most of the time, a counter-intuitive finding.

Looking forward

The emergence of open-source instruction-tuning data, algorithms, and models is one of the most exciting progress for LLMs in 2023. It gives researchers and developers the chance to train, evaluate, interact, and analyze instruction models with full control (from parameters to data), which only existed as black boxes before. The past few months are also a bit “chaotic” for the field, as hundreds of papers released results with different data, algorithms, base models, and even evaluation, making it hard to cross-compare the literature. I expect that the community will soon converge to some standard data/evaluation and we can develop better instruction-tuning models in a more scientific and reproducible way!

Acknowledgement: Thanks Tanya Goyal, Zhiyuan Zeng, Mengzhou Xia, Shunyu Yao, and Ben Eysenbach for their helpful feedback on the blogpost!

-

Open-ended instruction tuning should be distinguished from (multi-task) instruction tuning, which we will explain in details below. Here we use “open-ended instruction tuning” as an umbrella term to cover both supervised fine-tuning and the later alignment stage. ↩

-

The May2023-version LIMA only beats Alpaca—which imitates davinci003—and davinci003. It’s unclear how LIMA will compare to open-source models using other data. ↩

-

WebGPT (Nakano et al., 2021) also provides a preference data but it is tailored just for the WebGPT task format. ↩

-

This stage also involves “constitutional AI”, as the SFT model is prompted with “principles” when generating preferences. ↩

-

This method is never clearly mentioned in any paper and is only hinted by this OpenAI document. ↩

-

MT-Bench (Zheng et al., 2023) reports several human agreement rate. When including non-tie and tie (counts inconsistent votes as tie), the human agreement is 63%; when only including the non-tie votes, the human agreement rate is 81%. In both cases, it’s lower than the corresponding GPT-4 agreement rate to humans (66% and 85%). ↩